Due to the dearth of anything remotely compelling playing in the theatres, I have been turning my attention lately to my lengthening Netflix queue, in an attempt to somehow make a dent in its vastness. This past weekend brought me two long-overdue-to-be-seen titles, Raging Bull and Absence of Malice. The latter, a 1981 classic directed by the late, great Sydney Pollack and starring Sally Field and Paul Newman, is a dramatic and thoughtful treatise on journalistic ethics and it got me to thinking….what is it about journalism movies that make them so good? When I started to think of other movies about journalism, I found it astounding that the three titles that instantly came to mind just happen to be—in my opinion— three of the best films ever made. Not only the best films made about journalism, but among the best films ever made, period. Coincidence? I doubt it. I was determined to get to the bottom of it and figure out what exactly it is about these movies that makes them so darned excellent.

Absence of Malice (1981) Director: Sydney Pollack.

While the weakest film of the lot as a whole, Absence of Malice still delivers a powerful morality tale, asking all the right questions about where the lines are drawn for a journalist between “truth” and what is fit for print. Several themes are brought to the fore, including what makes something a fact and the media’s effect on our belief system, i.e., if it’s in the paper, it must be true. But where does that truth lie? Absence of Malice walks the very thin line between what a journalist can print and what they should print. The topics of sources, confidentiality, facts and what constitutes “news” are all addressed against a broader backdrop of how printed words affect human lives. In an odd way, the greater impact of this film seems like it would have been stronger for me if it hadn’t had Sally Field and Paul Newman in the leads. Back in 1981, they were the ultimate A-listers and while they are both extremely talented, they both just seem miscast here. Field just doesn’t have the fortitude to play a character who is in severe ethical crisis, while, at the same time, is trying to stand up for what’s right, while proving to herself and to everyone else that she’s up to handling the most difficult (and dangerous) stories. And Paul Newman playing the scion of a mafia boss? I just didn’t believe it for a second. But, all of that aside, Absence of Malice does have a terrific script, by Kurt Luedtke, which takes on all the right themes and offers an intriguing discourse on ethics and what lines you are willing to cross to break the big story.

Broadcast News (1987) Director: James L. Brooks.

One of the all-time greats, Broadcast News is exactly what I need and want in a movie: funny and smart. The smart comes in its seemingly all-too-accurate portrayal of the people who inhabit the network news—the producers, editors and anchors who we trust to tell us what’s going on in the world, and the funny comes from the knowledge that maybe we trust these people just a little too much. In no way a spoof or a full-blown satire, Broadcast News offers just enough cutting-edge insight into the machinations and manipulations of a network news broadcast while humanizing those responsible just enough to make them seem fallible, flawed and awfully funny. The irony in the fact that these people who we trust to tell us the state of the world and to offer intelligent analysis on the events of the day are also the most insecure, self-doubting and frustrated is not lost here. Network news is a real and important thing (or at least it was back in the days before internet) and Broadcast News treats it with humanity, humor and a healthy dose of skepticism. While Holly Hunter and William Hurt are the leads here, Albert Brooks steals the show with his dry wit and sarcastic one-liners. Everything about this film is first-rate and it guarantees you’ll never watch the evening news the same way again.

All the President’s Men (1976) Director: Alan J. Pakula.

The ultimate journalism movie. But what makes All the President’s Men different from all these other movies about journalism is it’s not about the journalists, it’s about the story. There is no time spent here dwelling on the character’s inner conflicts or emotional backstory. Instead, this film is a straightforward guys-doing-what-they-have-to-do-to-get-the-story tale. But what All the President’s Men does have in common with all of our other journalism movies is the focus on process. How does a story become a story? And what does it take to get it printed? Facts and sources are comingled with instincts and gut feelings and, as always, manipulations are everywhere as the motivation of every journalist remains the same: get the story. But when the story has implications and possible consequences as massive as the ones in All the President’s Men, the journalists become more than reporters, they become the conscience and advocate for the people and bring to the forefront the very essence of our republic: freedom of the press. Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford are both excellent in their portrayals of Woodward & Bernstein, the Washington Post reporters who broke the Watergate scandal, and Pakula’s moody and intense direction creates a tone equal to the subject matter. I can only imagine how many kids were inspired to be reporters after having watched this movie. Forget Clark Kent. Woodward & Bernstein are the real superheroes.

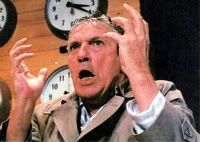

Network (1976) Director: Sidney Lumet.

Ah, the granddaddy of them all. Network is a chilling, scathing, brutal and cold-blooded look at network television and what it takes to survive in a ratings-driven world. While Broadcast News offered a light-hearted approach to the broadcast industry, Network is violent, taking a sledgehammer to any notion we may have that integrity, mutual respect and decency have any place in the world of marketplace media. Faye Dunaway encapsulates the ideal represented here, a self-serving, ladder-climbing, ambitious snake whose only interests are those that will result in the most money—and the highest ratings. She is the head of programming at the network and wants to take advantage of the on-air emotional breakdown that happens to one of the network’s newscasters, played by Peter Finch, who won a posthumous Oscar for his performance. Dunaway’s character, along with that of ruthless network president, played by Robert Duvall, will milk Finch’s character’s emotional state until every last drop of humanity has been wrung out of them—or until the ratings drop. Human consequence has no place in the realm of competitive programming, as moral, ethical and legal lines get crossed, all in the name of ratings. Magnificently scripted by Paddy Chayefsky, Network is incisive and biting, and one of the most powerful commentaries ever made on the power of television in our culture, and our allowance to be manipulated by its images and ideas. If you have not yet seen Network, you owe it to yourself to see it, as it is truly one of the finest films ever made.

No matter how you portray it, journalism and Hollywood seem to be a match made in heaven. These movies, along with many others, clearly exhibit all the drama, angst, ambition and ultimate search for truth that seem to lie at the heart of the journalistic profession. They offer a glimpse into our cultural psyche, for the way we receive and process our news is an inherent and relevant reflection of ourselves and our time. And it never hurts to see the world—and ourselves—for what it really is.

More journalism must-sees: The China Syndrome, The Year of Living Dangerously, The Killing Fields.